The traffic light hanging above our car is a blur of red. Tears are burning my eyes. Ryan is seated in the passenger seat next to me. He too is teary-eyed. It’s the eve of our big, 100-city book tour. The Florida sun has already set behind the Tampa Bay. Nightfall is upon us now. By the time the traffic light changes, it’s just a mess of wet green, a shapeless emerald cloud spilling into the nighttime ether.

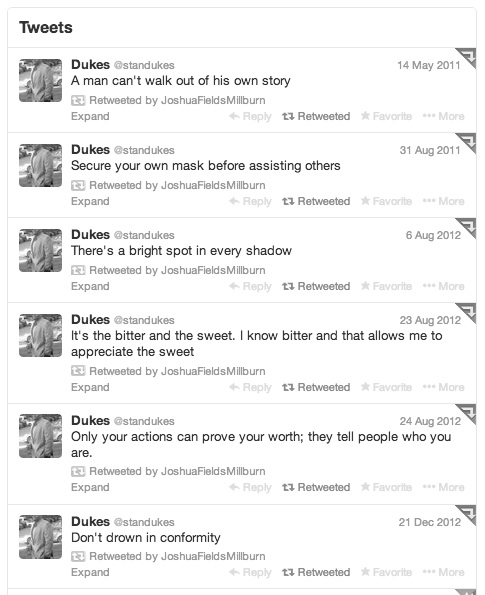

I received the call a moment earlier. The news: a week after Ryan avoided his own death, one of my closest friends, Stanley Dukes (pictured above), is dead.

This isn’t going to be easy to write. Overwhelmed with unanswerable questions, I feel a canyon of sorrow. Fuck, I can’t see past the tears. He was only 36, so I’m compelled to pen a thousands cliches:

Life is too short.

Every day is a gift.

You never know when you’re going to go so live your life to the fullest.

While all these truisms are apt, the truth is that Stan lived more in his three and half decades than most people could in 100 years. Stanley Dukes was a Mozart of positive living, and so his attenuated life was not in vain. Of course this doesn’t erase the pain, but it makes it easier to handle.

We met in the corporate world a decade ago. At first, when I was a regional manager, Stan worked for me as a store manager, but he was so talented—he added so much value to so many lives—that I often felt as though I worked for him. Although he managed dozens of employees, his genius was most pronounced in his ability to inspire people who weren’t self-motivated, which, if you know anything about leading people, is sort of like convincing water to be less wet. But somehow he did it, always carrying with him a smile and his “PMA” (Positive Mental Attitude). As a result, he was one of the most successful managers in the company.

Over time, we became close friends. We shared similar values and beliefs, as well as tastes in literature and movies and music: I traded him my overwrought short stories for his hilarious pseudonymous erotic fiction; we exchanged lines from Glengarry Glen Ross characters; and we both shared a healthy obsession for John Mayer’s music. We became so close that he is even the first person to make an appearance in my memoir, Everything That Remains, where he pops his huge, lovable head into the very first page:

Our identities are shaped by the costumes we wear. I am seated in a cramped conference room, surrounded by ghosts in shirtsleeves and pleated trousers. There are thirty-five, maybe forty, people here. Middle managers, the lot of us. Mostly Caucasian, mostly male, all oozing apathy. The group’s median complexion is that of an agoraphobe. A Microsoft Excel spreadsheet is projected onto an oversized canvas pulled from the ceiling at the front of the room. The canvas is flimsy and cracked and is a shade of off-white that suggests it’s a relic from a time when employees were allowed to smoke indoors. The rest of the room is aggressively white: the walls are white, the ceiling is white, the people are white, as if all cut from the same materials. Well, everyone except Stan, seated at the back of the room. Cincinnati’s population is forty-five percent black, but Stan is part of our company’s single-digit percentage. His comments, rarely solicited by executives, are oft-dismissed with a nod and a pained smile. Although he’s the size of an NFL linebacker, Stan is a paragon of kindness. But that doesn’t stop me from secretly hoping that one day he’ll get fed up with the patronizing grins and make it his duty to reformat one of the bosses’ fish-eyed faces.

Of course, Stan never would’ve touched a hair on any of their balding heads. He was above that. He was above all the petty bullshit we get caught up in every day. He was above living life based on other people’s standards. His standards were too high for that. He had character.

Stan contributed beyond himself. Each year at Christmastime, he dressed up as “Stanta” and handed out gifts to our employees. He spent many off hours donating his time to soup kitchens and Habitat for Humanity. Last year he founded a mentorship conference for young men ages 13–18.

Stan cared. When I decided to leave the corporate world three years ago, he didn’t flinch. Instead, he was the first to join me. We walked away together, guided by solidarity and a kinship that’s impossible to manufacture. Before I moved to Montana, we met for coffee weekly. Our visits yielded heartfelt advice on women and life, as well as arguments over which album was John Mayer’s best (Heavier Things or Battle Studies?). Everything about Stan reflected a profound Truth. Even his simple tweets were steeped in profundity:

Countless essays on this site were inspired by my conversations with Stan. Our final conversation was memetic of his life: it was short but meaningful. Three days before Thanksgiving I sent him a message: “I don’t have to wait till Thursday to be thankful for you. I’m grateful you’re in my life.” To which he replied succinctly: “Thanks for that. Know that I feel the same.”

Stan lived until he died. He truly lived. Every day. Not like most of us who walk through life like it’s some kind of dress rehearsal, worrying about bullshit that doesn’t matter. Nope, Stan was so alive, one of the only people I know who didn’t take this life for granted.

If there’s a lesson to be learned here, it’s that, like Stan, we’re all going to die, but few of us will be courageous enough to live as he did: honest, well-rounded, passionate, positive, and constantly improving. Above all, Stan Dukes was good people, a man I aspire to live like.

That green blur overhead is my signal to step on the gas, to wipe the tears and move forward. Perhaps you’ll do likewise. I know Stan would.